In 2018, pregnantish published an article shedding light on the untold lived experiences of Asian communities facing infertility. Seattle journalist and infertility advocate Annie Kuo shared her personal story of infertility as an Asian American, and captured insights into the cultural and societal experiences of Asian Americans with a clear message: if you’re in this community, you’re not alone. (See here for Annie’s 2018 piece Giving Voice To The Quiet: Sounding The Alarm For Asian Americans With Infertility). This pregnantish article has remained on the first page of Google when people search for the topic for a reason – there is inadequate representation and research conducted on the intersection of infertility and race, including how people of Asian descent are impacted by this disease.

Six years later, where are we? What has changed? And what has not?

With support from Generation Next Fertility in New York City and its Founder, Hong Kong born Reproductive Endocrinologist, Dr. Janelle Luk, pregnantish is continuing its exploration of this topic with a series of articles and a special pregnantish podcast episode.

As for me, I joined the pregnantish team over two years ago with a keen interest in aligning with pregnantish’s mission to amplify untold stories. I’ve been steeped in the world of reproductive health for over a decade – both my bachelor’s and master’s in Gender Studies specifically focused on women’s and reproductive health. My master’s dissertation aimed to unmask, disassemble, and analyze the worldviews and logics of Assisted Reproductive Technology (ART), highlighting global inequalities through an anti-racist lens. Though I myself am white, I’m proud to utilize the pregnantish platform to uplift the stories, work, and lived experiences of those traditionally left out in the story of infertility, like people of Asian descent.

The US Census Bureau defines “Asian” as: “a person having origins in any of the original people of the Far East, Southeast Asia, or the Indian subcontinent, including, for example, Cambodia, China, India, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, Pakistan, the Philippine Islands, Thailand, and Vietnam.”

This definition encompasses a diverse range of countries, languages, cultures, policies, and customs. So it goes without saying that it is impossible to capture the nuanced lived experiences of all people of Asian descent! But as a topic that doesn’t receive nearly enough attention, pregnantish is committed to creating openings for analysis and discussion.

Infertility affects 1 in 6 people, or 17.5% of the global adult population (and that’s what’s reported – we know this disease is underreported). In line with broader trends of inequity in healthcare, recent research demonstrates that infertility is more prevalent (read: under-treated) in minority patients than in white patients. And yet, infertility amongst Asian patients is highly under researched. In a literature review evaluating infertility amongst Asian American patients in the US, only 10 studies were found within the past 15 years.

Asian patients [are] highly under researched. In a literature review evaluating infertility amongst Asian American patients in the US, only 10 studies were found within the past 15 years.

While pregnantish cannot solve the limitation of lacking research and overgeneralized findings, this article strives to continue, and expand, the conversation.

Asian Fertility on a Global Scale

In recent years, the Asia Pacific Region has undergone major demographic changes. Governments in Asian countries have increasingly introduced and implemented policies to ensure sustainable fertility rates for years to come, including expanding access to childcare, offering financial incentives towards reproduction, providing easier workplace and work-from-home policies, and subsidies for assisted reproduction treatments, like IVF.

For example:

- Japan’s government enacted a policy to ensure that workers with children under three could request shorter work hours. Japan is facing a declining marriage rate, which contributes to its a declining birth rate, with recent research suggesting low sperm quality amongst young Japanese men.

- In Singapore, analysis has suggested that increasing reimbursement for Assisted Reproductive Technologies (ART) from $3,000 to $5,000 per cycle, for up to three cycles, would result in an additional 825 live births per year.

- As of 2023, egg freezing is now offered in Singapore to women ages 21-38 who wish to freeze their eggs for non-medical reasons. In fact, several countries in Southeast Asia now allow for “social egg freezing,” which refers to egg freezing with the goal to preserve healthy eggs without necessarily having a marital certificate.

- To attract higher rates of medical tourism, countries like Thailand have emerged as leading destinations for fertility treatment, combining affordable options with high-quality care in IVF, egg donation, and surrogacy.

- Commercial (i.e., paid for) third party reproduction is illegal in several Asian countries – e.g., commercial surrogacy is illegal in China and Cambodia, and commercial egg donation is prohibited in Japan and Singapore.

China: From The One-Child Policy to Subsidizing IVF

For 35 years, China maintained one of the most famous laws across the world: the “one-child policy.” In the late 1970’s, the Chinese government feared the growth rate of the country’s population was too rapid to be sustainable. So from 1980 until 2015, China’s one-child policy was a program that limited most Chinese families to reproducing one child each.

The social and cultural effects of this policy crystalized over decades and remain poignant today.

The one-child policy reinforced patriarchal attitudes and cultural preferences for sons, as it was believed that if a family could only achieve one child, a son would have a better chance of accessing education and/or providing for the family. This led to the abandonment of unwanted infant Chinese girls, creating what is known as a generation of “missing women.” In fact, Dr. Janelle Luk shares that her passion for women’s health was sparked from this very same piece of history:

“I went into medicine because I was fascinated by women’s bodies and empowerment since I was a little girl. This has to do with my mom’s trauma – she was given away as a child. Being a girl was labeled ‘bad’. Girls’ organs were ‘bad’, periods were ‘bad’ – the association of being a girl in China was not good. This was consistent throughout my childhood.”

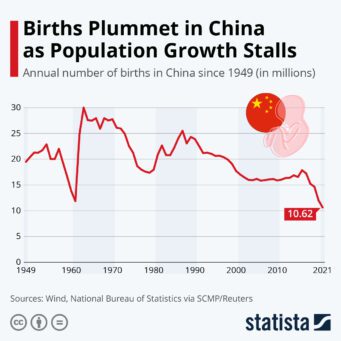

In 2015, as projections for China’s population continued to plummet, the government finally raised its limit to two children; By 2021, the policy allowed for three. Months later, the Chinese government removed all limits on reproduction. After the policy was lifted in 2021, the government quickly pivoted to provide financial incentives to encourage having more children. In 2023:

- The Chinese government wants to make ART (which it made legal in 2001) more accessible. It has promised to cover some of the cost under national medical insurance.

- China’s National Health Commission urged central and provincial governments to increase spending on reproductive health, and improve childcare services at the national scale.

- China’s State Council said it would roll out new measures to encourage flexible working hours, and an option to work from home for employees with children.

- Local authorities are slated to offer preferential housing for families with multiple children, such as providing larger public housing apartments.

- In Shenzhen, a city in the Southern region of China, the government provides couples having a third child or more with an allowance of 6,000 yuan ($890).

Representation Matters: Dr. Luk’s Perspective as an Asian Fertility Doctor

I had the privilege of connecting with Dr. Janelle Luk, Medical Director and Co-Founder at Generation Next Fertility, about her experiences as an Asian American, Reproductive Endocrinologist, and Infertility Specialist.

Dr Luk shares that from a young age, she had curiosity and passion for women’s health and was proficient in subjects like math and science.

She shares, “When I learned about the woman’s body, I said, ‘oh my god, this is so magical. You can house a life, you have a uterus that regenerates linings, you can make a placenta!’ I discovered it was the social construction, perspective, culture and optics that made being a woman look bad. And that fascinated me. Since then, I’ve wanted to dedicate my entire life to women’s health and empowerment. And that’s why I went into medicine.”

(In my culture) the stigma of women’s bodies is big. There is a culture of not talking about the body, or not celebrating the body. No one wants to discuss the reason why (you don’t get pregnant). Growing up, the general perception was that it’s always the woman’s fault, which isn’t true, as 30% of infertility is on the male side, 30% on the woman’s side, and 30% is shared. In my family, my godmother never had children, but no one talked about why – maybe it was my godfather who didn’t have sperm, but generally the blame is on the woman. To my patients that share a similar cultural background, I give the advice – ‘your body is not dirty, you should talk about it! And seek care.’ The perception of the female body should be positive in Asian communities, and one should be empowered to understand their body parts.

(In my culture) the stigma of women’s bodies is big. There is a culture of not talking about the body, or not celebrating the body.

Gender discrimination exists everywhere, not just in Asian communities, and as a result I don’t know if everyone has the awareness and access to care they need… That’s why my goal as a doctor is not just to treat my patients, but to inform them as a way to empower them. Women may see a period as a nuisance, instead of understanding puberty and why the menstrual cycle is essential in reproductive biology. They might not know about endometriosis, they may assume period pain is normal. It’s about how one’s empowered to understand one’s body. If that kind of empowerment could be celebrated in Asian communities, then more Asian women could have access to care.

Additionally, in top-down Asian cultures, many of us will try to make our parents happy. Because of that, we develop people-pleasing tendencies, and we may be anxious about what other people want. However, when it’s about your life, and your body, and having a child, there is no need to people-please anymore. Some of my Asian patients come to me to say, ‘I’m here because my in-laws want a son.’ Or ‘someone in my family wants a boy or girl because it’s the Dragon year.’ I always say, ‘Don’t have a child to save the marriage or to please your parents!’ I’ve seen this pattern very many times. If you’re going to (have a baby), do it for yourself.’

I think one of the major barriers is the perception of fertility care. There is the false idea that the baby being produced is artificial. Ignorance, lack of knowledge of what fertility care or IVF really is, is a big barrier for many Asian communities. IVF, and other reproductive technologies, are a valid path to parenthood, and I’m proud to be an advocate for women who may feel as though this is a silent struggle.

That’s why I’m proud to be the Medical Director and Co-Founder of Generation Next Fertility, where I can empower the Asian community by offering support and resources. We have a concierge patient liaison who speaks Chinese. I also speak Chinese and Cantonese, both dialects. Our website also has a Cantonese version to educate our Asian community and be as well positioned as possible to care for Asian communities experiencing infertility. What I love most about Generation Next Fertility is that it’s a safe space for Asian couples struggling with infertility to have an open and honest conversation with a team that understands not just how delicate the fertility journey is, but also recognizes the cultural and emotional aspects that can sometimes make the Asian fertility journey exceptionally distinct.”

Masculinity + Infertility: 30 Million Men Worldwide

For heterosexual couples, around 30% of fertility problems originate from the man – with some citing even higher numbers. Major causes include obstructions to the passage of sperm, low sperm count, poor quality sperm, functional challenges (i.e., impotence), and hormonal problems. Though on a global level there is a lack of accurate statistics on rates of male infertility, recent research suggests at least 30 million men are affected by infertility, with highest rates found in Africa and Eastern Europe.

We also know that a big focus now is on declining sperm rates in Asian countries like Japan. According to an updated review of medical literature, human sperm counts appear to have decreased by more than 50% in the last 50 years around the globe, with higher concentrations in Asian countries.

We also know that a big focus now is on declining sperm rates in Asian countries like Japan. According to an updated review of medical literature, human sperm counts appear to have decreased by more than 50% in the last 50 years around the globe, with higher concentrations in Asian countries.

One of the most potent challenges of male infertility is the stigma associated. The pressure of patriarchal norms worldwide has led to patients with male infertility often citing shame or feelings of emasculation. Many men become reluctant to seek medical help, which can delay treatment and further worsen clinical outcomes. While this is true across almost all cultures, infertile men may face extra pressure in Asian societies, which are often patrilineal, meaning that males are expected to have male children to continue the family bloodline.

More storytelling and diverse representation is crucial to continue normalizing the conversation about male factor infertility, and the experiences of infertility globally.

Where We’re Headed

Birth rates in Asia are dropping, and rates of infertility are on the rise (or at least are now reported more inclusively). CDC and SART data showcase that although Asian patients were reported to have worse outcomes compared to their white counterparts, there is also an increase in ART utilization amongst Asian communities.

Annie Kuo explains: “Asian Infertility is still very understudied. Since my first piece on Asian Infertility was published on pregnantish 6 years ago, there have been a couple more studies done, but I would say that Asians in reproductive medicine and family building have not reached the same level of substantial changes as say, Asians in Hollywood. Now we’re seeing Asian representation on the big silver screen, Asians emceeing the Golden Globes, receiving Emmys, Oscars – which is long overdue. But the same changes are not happening in the world of reproductive medicine and family building.

I think medical residents and fellows in reproductive medicine should be trained to customize medical protocols for Asian patients and other patients of color. That’s the missing piece that would change healthcare for Asian infertility patients. Doctors should be able to go to professional conferences, hear research that is done on Asian infertility or for people of color, take it back to their clinics and hospitals, and apply custom protocols. There should be a shift of medical education for fellows and residents. For example, doctors I’ve spoken to who’ve done research (in this category) cite that the uterine environment in Asian women is more receptive to fresh embryo transfers rather than frozen. This type of culturally-sensitive protocol can really move the needle towards better care for Asians.”

Our upcoming piece, part two in our three-part series on Asian infertility, focuses on the importance of breaking stigmas for improved clinical outcomes and expanded access to care. It is critical to draw the curtain back on the lived experiences of those affected by infertility around the globe in order to shatter taboos and make sure everyone in this community knows they are not alone in this experience.

Pregnantish is committed to upholding our “Real Talk About Fertility” mission and uplifting the stories of those who are often left out of the conversation about infertility. As we provide more education and break existing taboos (coming up in our next pregnantish piece and on our podcast!), we hope that more people of Asian descent who need ART to build their families will be able to access the care they deserve.

This article is supported by Generation Next Fertility in New York City, whose mission is to provide individualized patient centric quality care and innovative technologies to help patients become parents. For more, visit generationnextfertility.com

Contributor

Carolyn Kossow

Carolyn Kossow (she/her) is a gender, queer, and racial justice communications professional and activist based in Brooklyn, NY. She received both her Masters and Bachelors degrees in Gender Studies (London School of Economics and Hamilton College, respectively) with a focus on reproductive health, and is dedicated to a life and career advocating for social justice. Carolyn supports the work of pregnantish through subject matter expertise, content creation, and project management. Carolyn’s work and research has utilized critical-race, queer, and feminist theories to examine reproductive health injustices worldwide with specific focus on racism and classism within assisted reproductive technologies (i.e., egg donation and surrogacy). She has worked in several nonprofits and start-ups advocating for economic, racial, LGBTQ, and gender justice at a local and global scale.

Listen to stories, share your own, and get feedback from the community.